One of my favorite kinds of literary formats in high school was (and still is) the Science Fiction Anthology. A grab-bag of styles and ideas, I never knew what to expect. Greedily pulling down every Nebula Awards, Science Fiction Hall of Fame, or Year’s Best SF, I was introduced to editors like Asimov, Bova and Greenberg, and untold numbers of authors. It was how I first learned about Ray Bradbury, Alfred Bester, Philip K. Dick, and James Tiptree, Jr. I knew Frank Herbert from his weird short stories long before I ever cracked open Dune.

Most of these stories were from the ’50s and ’60s, and with them an obsession with the early Cold War, healthy dollops of sexism, and equally incomprehensible (to me) allusions to the Bible. But the stories stayed with me, some fondly resurfacing from my literary past, perhaps now making more (or less) sense to me as I got older.

Most of these stories were from the ’50s and ’60s, and with them an obsession with the early Cold War, healthy dollops of sexism, and equally incomprehensible (to me) allusions to the Bible. But the stories stayed with me, some fondly resurfacing from my literary past, perhaps now making more (or less) sense to me as I got older.

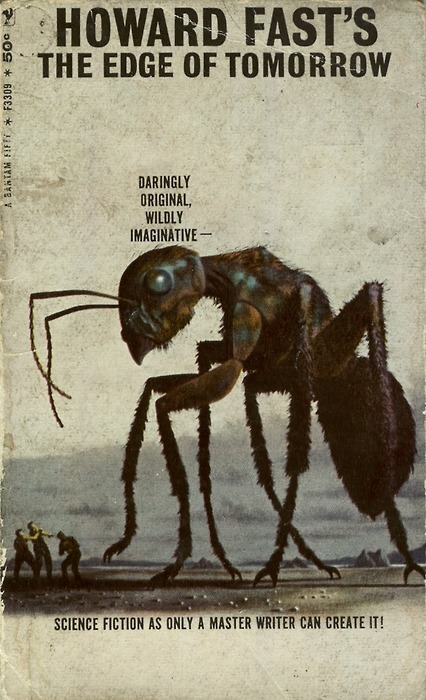

One of these stories resurfaced recently, a very short 1960 story by Howard Fast titled, “The Large Ant”. I had no idea at the time of Fast’s repertoire, but of course any short story about large ants was bound to leave an impression on me. I recently got hold of an old paperback by Fast containing that story, and re-read it after 25 years. The paperback has a glorious uncredited cover showing a colossal ant terrorizing puny humans on the cover. Which is even more amusing when you realize that Fast’s tale is about an ant a 100th of that size, though the fear factor is the same.

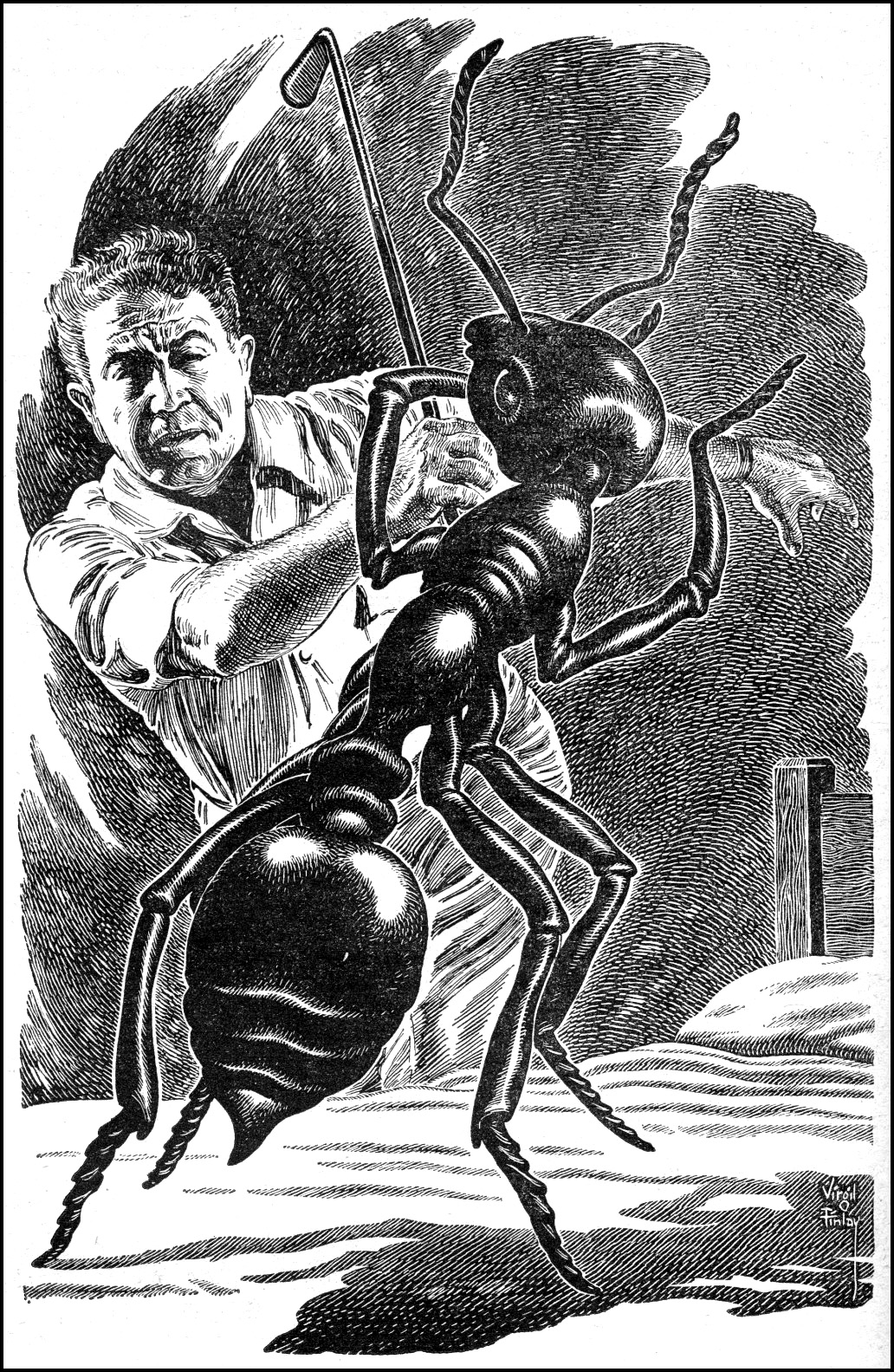

In the story a man on vacation named Morgan finds a large ant, “fourteen inches long” slowly crawling on his bed. Instinctively he grabs a golf club and kills it dead. Later he takes the carcass to an entomologist, who is curiously joined by two representatives from the government, and they are all gravely interested in Morgan’s find.

Lieberman said, “You are an intelligent man, Mr. Morgan. Let me show you something.” He then opened the doors of one of the wall cupboards, and there eight jars of formaldehyde and in each jar, a specimen like mine- and in each case mutilated by the violence of death.

Lieberman closed the cupboard doors. “All in five days,” he shrugged.

“A new race of ants,” I whispered stupidly.

“No. They’re not ants. Come here!” He motioned me to the desk and the other two joined me. Lieberman took a set of dissecting instruments out of his drawer, used one to turn the thing over and then pointed to the underpart of what would be the thorax of an insect.

“That looks like part of him, doesn’t it, Mr. Morgan?”

“Yes, it does.”

Using two of the tools, he found a fissure and pried the bottom apart. It came open like the belly of a bomber; it was a pocket, a pouch, a receptacle that the thing wore, and in it were four beautiful little tools or instruments or weapons, each about an inch and a half long. They were beautiful the way any object of functional purpose and loving creation is beautiful- the way the creature itself would have been beautiful, had it not been an insect and myself a man. Using tweezers, Lieberman took each instrument off the brackets that held it, offering each to me. And i took each one, felt it, examined it, and then put it down.

I had to look at the ant now, and I realized that I had not truly looked at it before. We don’t look carefully at a thing that is horrible or repugnant to us. You can’t look at anything through a screen of hatred. But now the hatred and the fear were dilute, and as I looked, I realized it was not an ant although like an ant. It was nothing that I had ever seen or dreamed of.

All three men were watching me, and suddenly I was on the defensive. “I didn’t know! What do you expect when you see an insect that size?”

Lieberman nodded

“What in the name of God is it?”

“We don’t know,” Hopper said. “We don’t’ know what it is.”.

The story turns on the assumption that human nature is unalterable, and that humans are instinctively afraid and horrified by the unknown in general, and insects in particular. When Morgan kills the large ant, he can’t even bring himself to look at it due to shaking disgust and fear. And now his human nature, the “curse of fear,” has resulted in the death of an intelligent being;

I keep trying to drag out of my memory a clear picture of what it looked like, whether behind that chitinous face and the two gently waving antennae there was any evidence of fear and anger. But the clearer the memory becomes, the more I seem to recall a certain wonderful dignity and repose. Not fear and anger.

…

“But tell me – where do these things come from?”

“It almost doesn’t matter where they come from,” Lieberman said hopelessly. “Perhaps from another planet- perhaps from inside this one- or the moon or Mars. That doesn’t matter. Meanwhile, they have the problem of murder and what to do with it. Heaven knows how many of them have died in other places – Africa, Asia, Europe.”

During a time of intense anxiety from the threat of nuclear war, it wasn’t a stretch to assume an alien intelligence would be met with fear and violence from our species. in 1960, it seemed like we were ready to extinguish ourselves with both. The story ends with Morgan and the other gentlemen waxing fatalistic about humanity’s chances. After all, who can resist killing a large insect?

Well by this time you probably guessed, even when I was a young lad I found this conceit rather implausible. Ask anybody who loves insects, or biology in general, and I think their first instinct would be not to kill, but to capture, or at least properly ID a fourteen-inch ant. I believe further that entomophobia and arachnophobia are not instinctive, but learned traits. Children need to be taught to fear spiders and beetles. Toddlers have only fascination at the curious creatures that are down at their level. But it doesn’t take long to walk about and find a grown adult who is scared pantless by the sight of a cockroach, or house spider, or any other invertebrate. In California especially, where disease or injury from insects is especially rare, people run screaming from harmless Jerusalem crickets, of all things.

Which is why this story struck a chord with me then as it does now. If we can’t find awe and wonder in our fellow life forms on Earth, how will we fare when tick-shaped aliens from Planet Ixodon come calling? Probably still rather poorly, but better than Howard Fast’s prediction. I also like to think we’ve advanced a little farther through education about the world we live in. If the “curse of fear” is learned, so can the “curse of curiosity”. To paraphrase Kermit the Muppet, That’s the kind of curse that gets better the more people you share it with. ![]()

One Response to The Curse of Fear