Is there anything more magnificent than viewing an organism in its natural habitat? For years I have wanted to view horseshoe crabs alive and swimming, but never found a reason to visit the East Coast during those beautiful Spring months… until now!

By chance our friends’ wedding in Boston took place during the same time that horseshoe crabs haul out of the muddy depths to mate and lay eggs along the Eastern shore. A full moon was scheduled that Friday, so Mrs. Swarm and I planned an escape to drive as far South as we could manage, to the sandy shores of Cape Cod in hopes of viewing live Horseshoe crabs. At last I would be able to lay eyes on something I’d wanted to see for decades.

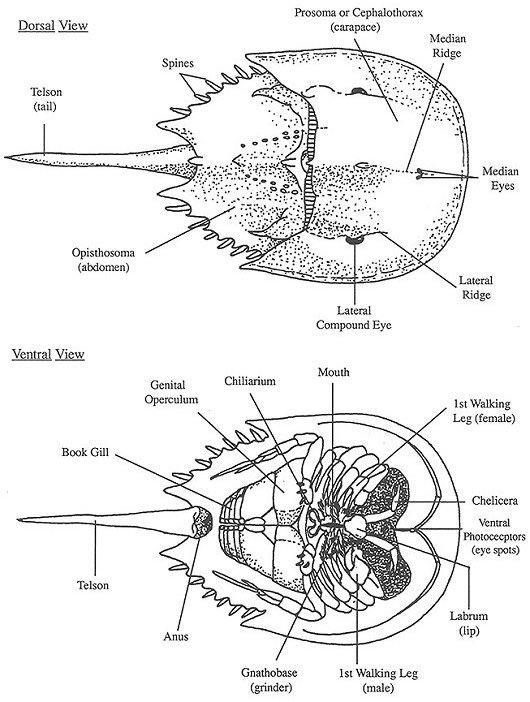

But first a quick introduction. Three of the four species of horseshoe crabs are found in the seas of Southeast Asia, except the biggest, Limulus polyphemus. Except for the lucky ones who have lived on the Eastern Coast of the US, most humans will never meet an Atlantic horseshoe crab. And that’s sad, because they’re just busting out with insane otherworldly magnificence. Horseshoe crabs are arthropods, but aren’t actually crabs. In fact, they’re not even crustaceans. Horseshoe crabs are a member of the chelicerata, a group that includes scorpions and other arachnids. If you turn one over, you can see the resemblance in their four pairs of legs, and pedipalps. It looks like a giant hairless tarantula! It’s especially enthralling because that means I’m looking at a relative of the great sea scorpions and eurypterids that ruled the warm seas of the ancient world. Of those great marine chelicerates, only the horseshoe crab remains, its fossil record going back some 450 million years. With all the continental drift, mass extinctions and new phylums popping up over the millenia, somehow there was always a nice muddy silty place for horseshoe crabs to amble about in. They’re true survivors, though it’s somewhat misleading to call them ‘living fossils’, as they have in fact evolved quite nicely over time, thank you- It’s just that they’ve been evolving into nearly the same thing for 450 million years. Few organisms in Earth’s history have matched that trick. (For more about horseshoe crab evolution and their unique physiology and anatomy, check out horseshoecrab.org)

We drove our rented car down Highway 6 on a rainy, grey late May morning. Not the best for crab-viewing, but this was our one chance to get to a high tide during the full moon. All of Cape Cod was brilliant green, the trees filled thick with tender fresh leaves, as we pulled into the Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, located in the inner curl of the cape. The woman behind the desk was overjoyed that we came all this way to see horseshoe crabs, though she said populations still have not recovered from overharvesting. “I used to go out to Wellfleet in the 80’s, and the shore would fill with them… now they’re far fewer.”

Wind and rain pelted us as we made our way through the sandy forest. All the while I would peer past the great reedy salt marshes, looking out for the sandy bays where they would most likely haul out. In the Northeast, tides are serious business, and all the wooden walkways were knee-deep in rushing water. The coast was full of sea wrack that held all sorts of things common to the Atlantic Coast, but wonderous to behold when you’ve lived your life by the Pacific. Whelk egg cases! Moon snail shells! Skate egg cases with their twisty spines! Fiddler crabs clambering about fingery seaweed and decaying piles of reeds!

Plus flocks of shorebirds, feeding excitedly before the oncoming ocean closes over their sandy dining table. At first the only horseshoe crab we could find was one high up on the shore, long dead. I picked up its body and was using it to illustrate the finer points of Xiphosuran anatomy, when two of my friends discovered two living horseshoe crabs, flipped over from the rushing water.

They’re SO BIG! Note the white slipper shells attached to the underside. Also, if you find a flipped horseshoe crab, do your part and help it over! Photo by Loganinsky

A male and a female were using their telsons to help flip themselves over, though the male was still trying to grip the female’s opisthosoma with his pedipalps all the while. Both were absolutely encrusted with all manner of hangers-on: slipper shells, barnacles, and seaweed. Horseshoe crabs stop molting after about 9 years of age, but otherwise age is difficult to determine. These two could have been anywhere from 10 to 30 years old. I gently picked up each before placing them back in the water, to feel their great heft and sturdy muscular action, and gaze into their endearingly serious compound eyes. To me holding a horseshoe crab… is like staring down into the Grand Canyon, where the great majesty of deep time is laid out in a way that you can see and touch. Start at the crest of the immense canyon and start your hike down. How does one really grasp 100 years ago? A thousand? Before humans? Before mammals? Before dinosaurs? Keep walking downhill buddy, you’re not even close. Before amphibians? Before insects? Now you’re getting somewhere. Horseshoe crab fossils have been found in strata that predate vascular land plants. We’re talking moss, people. And that 445 million-year-old’s relative is staring right back at me, a wobbly mass of striated muscles that grew limbs and lungs and prehensile thumbs who can do nothing but gape slack-jawed in wonder.

I was hungry to see more. I spied waves curling way out into the sea, surrounding the salt marsh bay known as a haven for immature horseshoe crabs to develop. My companions and I pulled up our pantlegs to no avail- we were entirely soaked. Pretty soon we reached a slightly raised sandy spit that was hidden beneath the water, and there they were. Horseshoe crabs! Not many, just in ones and twos, scooting like huge marine Roombas over our feet and between our legs. Even though they look big and spikey, they’re slow and so gentle. They don’t pinch, bite, or poke, or sting. We found one very large female with two males clutched to her back, forming a silent conga line as they looked for an easy access to the shore.

Crossing the Atlantic, on the lookout for Xiphosurans. Photo by Pecksniff Wallydrag

Not an hour later, the wind and rain really picked up, and it was time to head back to land, and hopefully a warm meal. Though in all we only saw a couple dozen horseshoe crabs, I felt ecstatic. Seeing them in the wild, not in an aquarium nor in a museum, was such a thrill.

Though in the end I was glad to wait out the rest of the rainstorm in a lovely Provincetown cafe with my friends, by no means am I satisfied. On the contrary, I’m even more obsessed. Next year, I’m going to make good on my invertebrate tourism goals, and get to where the Atlantic horseshoe crabs congregate in absolutely huge numbers.

Next year, I’m going to Delaware Bay! ![]()

One Response to The Grand Canyon In My Hand