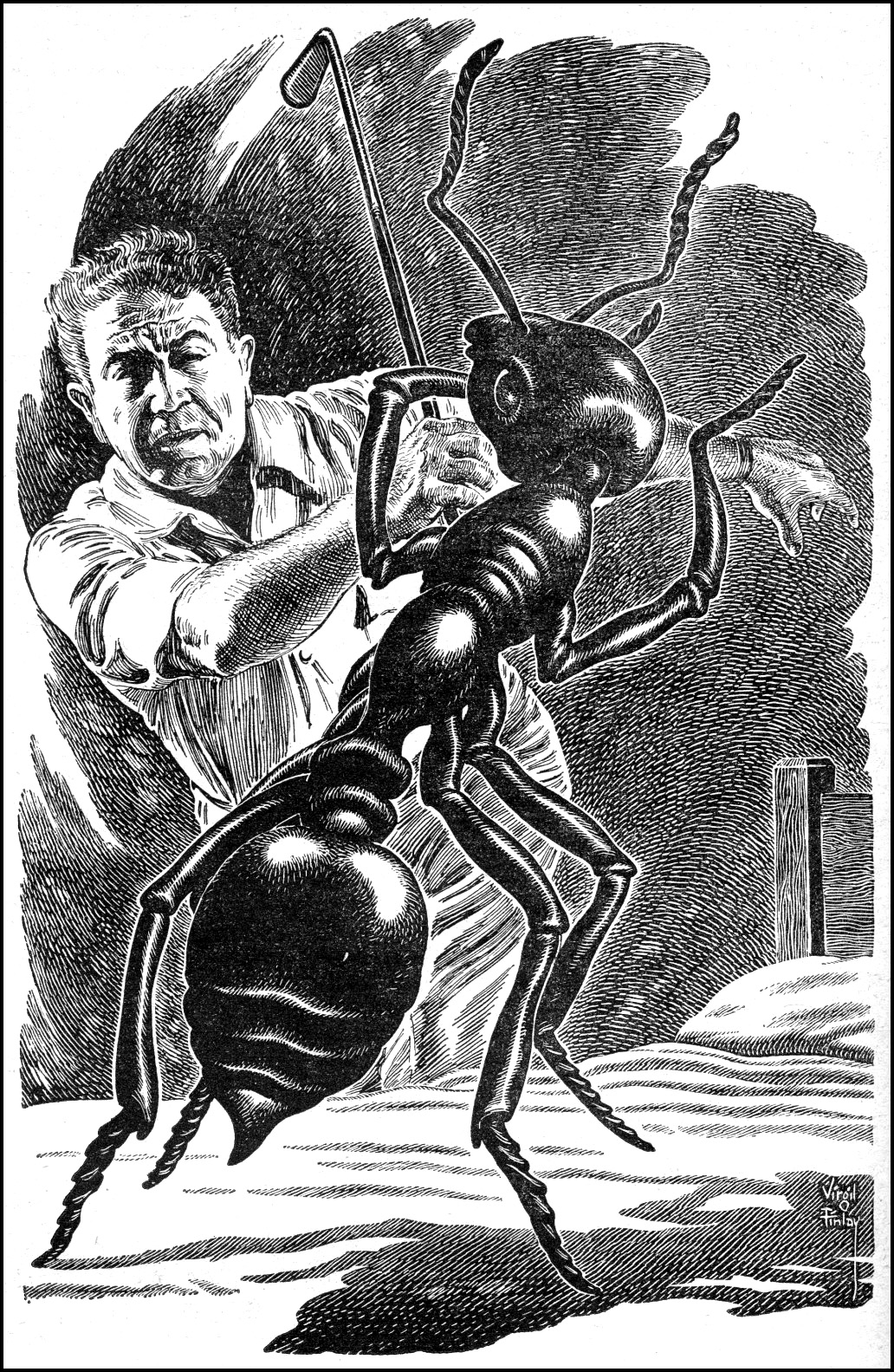

October is a great time for the staff here at the Endless Swarm. It’s the one time the rest of the world seems to pay attention to the world of the unloved invertebrate. Entomological festivals get scheduled, museums dust off their insect zoos, and every creeping crawly swells and mutates to the size of city blocks. Well, in movies and fiction at least. To kick off a grand tour of this month’s Brobdingnagian bugdom, we go back to the start of last century:

“In the following article the insects and scenes represented are from actual photographs”

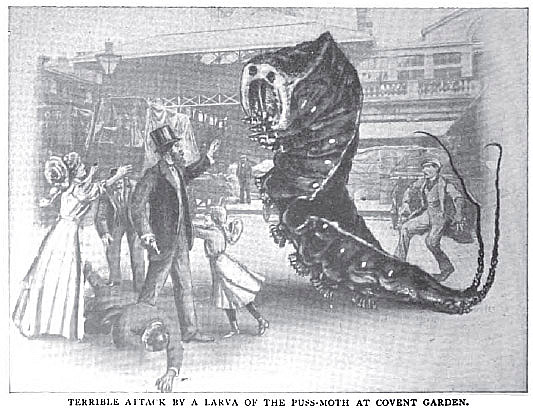

In 1910 The Strand magazine published an amusing article about giant insects. Though the chaps at Futility Closet were kind enough to post the images for all the world to LOL at, I wanted to read the rest of this essay. Anything that doesn’t have a source makes me a bit hoax-suspicious, so naturally I wanted to hunt down the original article. Thankfully the full article is here in PDF form, and contains all manner of delightful forays into the chaos that would ensue from giant invertebrates running amok! I would love to share with you some of the choicer paragraphs (as well as the original images) below.

e are, are (save a few contented ones) so apt to be perpetually complaining of the disadvantages and drawbacks of life that we hardly even stop to realize how much more severe and discouraging mundane conditions might be. Suppose the temperature of a really hot day were two hundred degrees Fahrenheit in the shade, instead of a paltry eighty-five or ninety! Or one hundred below zero on a wintry one! Then we might really complain if hailstones were of the size and shape of cannon-balls, and it hailed twice a week.”

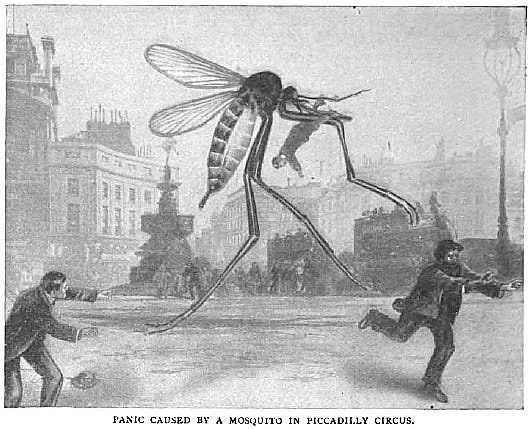

“Or take our insect pests. What a terrible calamity, what a stupefying circumstance, if mosquitoes were the size of camels, and a herd of wild slugs the size of elephants invaded our gardens and had to be shot with rifles, unless Maxim guns were to be employed for the purpose! Truly, in these respects we are a lucky race, living under almost ideal conditions.

It is true we are still molested by hordes of wild animals of bloodthirsty propensities. These wild animals only lack the single quality—namely, that of size—to render them all – powerful and all – desolating, and this quality they have not been able to attain owing to the lack of favouring conditions.

How easily it might be otherwise. Suppose, for example, that a few yards from the office of this Magazine, in Covent Garden Market, a terrible Fuss – moth larva were to have escaped from his cage or his keeper—if, indeed, he were not to have developed into gigantic proportions in a single night—what a panic would be caused!”

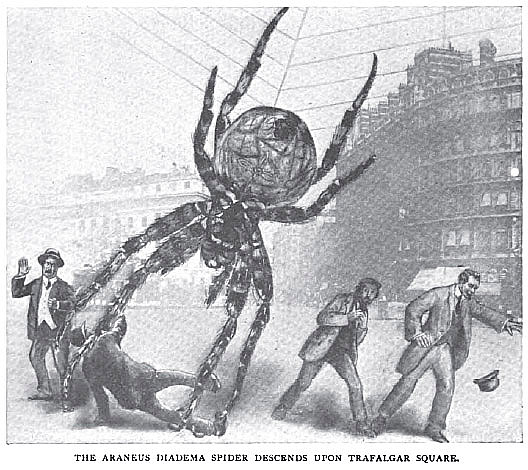

“One day we will imagine London to have been startled by the sudden visitation of a monster Araneus diadema, somewhat larger than a mammoth, which, descending upon Trafalgar Square, seized a number of pedestrians in its jaws, and, having hastily dispatched them, proceeded to knock over a couple of the Landseer lions, under the impression that they were animated by hostile feelings, overturned a motor-bus, and, after doing as much damage above-ground as possible, insinuated itself into the Trafalgar Square station of the Underground Railway, where it became wedged in the tube, and was finally dispatched by concussion of the brain through colliding with an electrically-driven engine.

Yet the Araneus diadema has frequently been seen in the neighbourhood of Trafalgar Square. It is easy to imagine them hiding themselves in their silken cells spun amongst the leaves of the plain trees that adorn the Square; or hidden in the stones of the classic front of St. Martin’s Church. Only instead of being twenty or thirty feet in diameter, the spider with the foregoing name is but half an inch or so from head to tail, which, as I said before, ought to be regarded as a great mercy to mankind.”

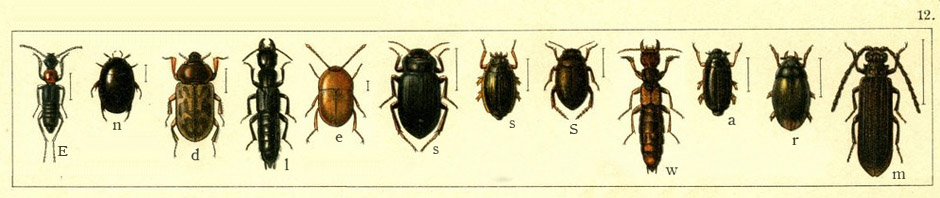

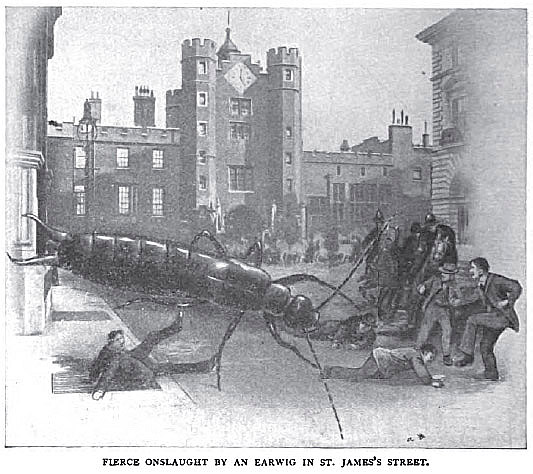

“Then we may easily fancy ourselves reading of the tragedy of the Dermapteron which one fine night tore out of the St. James’s Park, and for twelve hours held the fort at St. James’s Place until a regiment of soldiers succeeded in giving the grim monster his quietus. But at what cost! Eighty and more citizens and soldiers lay dead or mortally wounded at the bottom of Pall Mall. And the Dermapteron is not an imaginary insect, springing from the brain of Mr. Kipling or Mr. H. G. Wells, but our old familiar friend the earwig. A nocturnal insect is the earwig, with curved forceps at the end of its tail. They do not fly by day, but are very wide awake indeed at night, taking food and committing their depredations, as every gardener will tell you.”

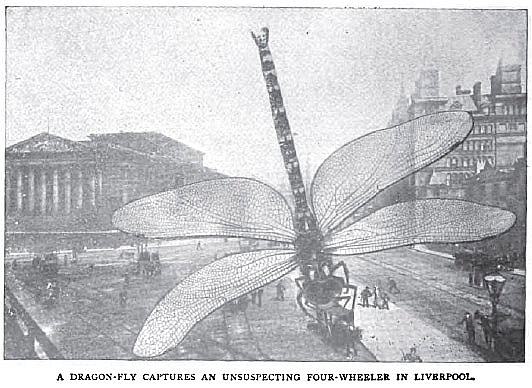

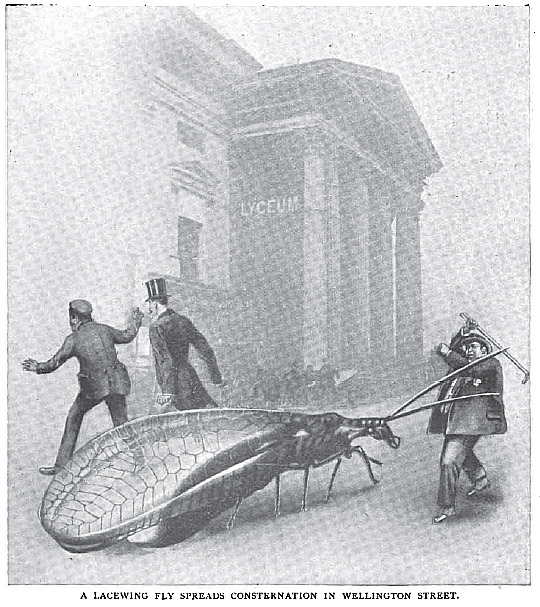

“The lacewing fly, as my readers are aware, is a small, delicate insect with long and richly-veined wings of a tender green colour, like that of the body. Its antennae are long and tapering, and its prominent eyes shines like hemispheres of gold.

From this description we may surmise that were a lacewing fly to spring suddenly into magnified existence somewhere — say in the neighbourhood of the Lyceum Theatre, not magnified as we see it under a microscope, but a millionfold, the size of a monster alligator — the consequences, besides creating the utmost panic and alarm common to every cab accident, might be of a very serious nature, if they were seized with an appetite for walking gentlemen, chorus “ladies,” or even the harmless, necessary supernumerary.”

Though I detect a healthy dose of entomological education in Mr. Kerner-Greenwood’s writing, most of the other articles written by him are all dry reference works concerning architecture. What brought this lovely gem into existence, we may never know, but it makes me mighty happy. ![]()

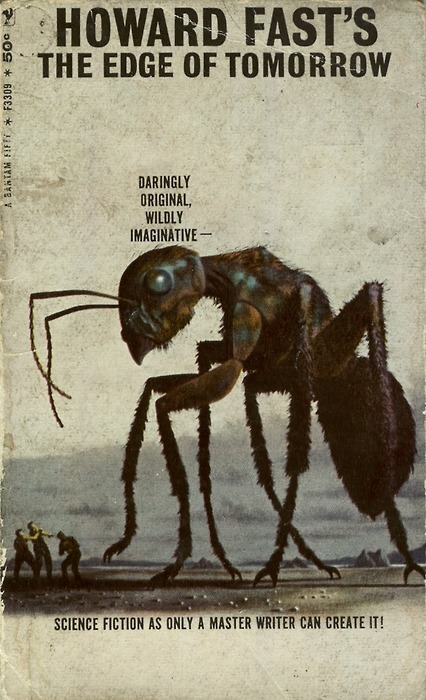

Most of these stories were from the ’50s and ’60s, and with them an obsession with the early Cold War, healthy dollops of sexism, and equally incomprehensible (to me) allusions to the Bible. But the stories stayed with me, some fondly resurfacing from my literary past, perhaps now making more (or less) sense to me as I got older.

Most of these stories were from the ’50s and ’60s, and with them an obsession with the early Cold War, healthy dollops of sexism, and equally incomprehensible (to me) allusions to the Bible. But the stories stayed with me, some fondly resurfacing from my literary past, perhaps now making more (or less) sense to me as I got older.