Like the endless nature documentaries that invariably used a football field as the default unit of measurement for flea-jumping, nearly every educational book or film that mentions spiders always talked about the incredible unrealized potential of spider silk. “Pound for pound, it is stronger than steel!” Other books got people to imagine what the properties of commercial spider thread would be like, if only it could exist, because of course it can’t. For somebody who consumed a metric ton of educational books about insects and spiders, such repeated factoids became tiresome. To paraphrase Warner, everybody talks about spider silk, but nobody does anything about it.

Which is what I initially assumed must have been what went through the minds of Simon Peers and Nicholas Godley when, after careful research, they attempted to actually put theories and history to test and weave silk thread from Nephila madagascariensis, the giant golden orb spider. The result is more than just an arachnological and sericultural curiosity. It’s a technical, artistic, and community-based triumph of the first order, an absolute wonder to behold. I know this for a fact, because I finally got to beholdify it with my own eyes at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it is on display for only another month! A happy coincidence with my brother-in-law’s wedding allowed me time to visit with family, so long as I could drag them with me to to the museum!

In this picture: myself, and the combined effort of a hundred humans and millions of arachnids.

Though I had read all about the history of its creation, there’s nothing like seeing such a thing in person, to peer at the fine diaphanous silk tassels, or to watch the light catch the traditional patterns woven throughout. Despite its near-radioactive hue, the tapestry is in no way dyed. That’s raw Nephila silk, folks. Fascinatingly, the color is influenced by the spider’s diet. Subtle variations in the silk from each spider were evened out as the silk was mixed, lending it a uniform quality of golden brilliance.

Unlike hapless silkworms, cultivated by endless amounts of mulberry leaves, spiders are a limited wild resource, and while docile, are in no way domesticated. I love the descriptions of the weavers’ catch-and-release program:

- “The spiders are harnessed … held down in a delicate way,” Godley says, “so you need people to do this who are very tactile so the spiders are not harmed. So there’s a chain of about 80 people who go out every morning at four o’clock, collect spiders, we get them in by 10 o’clock. They’re in boxes, they’re numbered, and then as they get silked, about 20 minutes later, they get released back into nature.”

If you haven’t seen it already, I highly recommend this 10-min video put forth by the Chicago Art Institute. It’s well done, and it also partially answers something that has been bothering me for a while, mostly about the history of spider sericulture. Most articles make light reference to the fact that spider silk was “tried once in the 1800s, then abandoned”, or other such one-liners. The AIC’s site, and their video, has a bit more:

- “The idea of harnessing spider silk for weaving is an age-old dream that was first

attempted in a methodical way in France in the early 18th century. In the 1880s,

Father Paul Camboué, a French Jesuit priest, brought the dream to Madagascar.

Intrigued by the strength and beauty of the silk produced by the island’s golden orb

spider, he began to collect and experiment with it. In 1900 a set of bed hangings

was woven from spider silk at Madagascar’s Ecole Professionelle and exhibited at

the Exposition Universelle in Paris (today the whereabouts of those hangings are

unknown). But the idea of creating an industry that could compete with Chinese

silk (produced from silkworms) proved unrealistic. “

But who is this guy Camboué ? Sadly, even pictures of the fellow on the internet are hard to come by, though there’s a couple in the AIC video. He looks like an interesting character, and after a little digging I was able to find this lovely account:

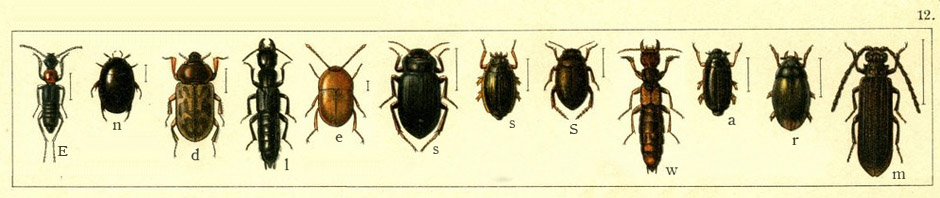

- Camboué was prolific, and produced a variety of written works. He was a “bush missionary” who largely worked west of the capitol, in Arivonimamo and Ambohibeloma. He related his concerns to others in a steady stream of correspondence, and many of his letters were published in missionary journals of that time. He was also interested in studying Malagasy behavior and morals, customs, and art. However, his renown came largely through his accomplishments in the field of natural science, principally in the study of invertebrates.

The link here has but a partial list of his contributions to entomology. In my opinion Father Camboué was kind of a badass, the sort of unstoppable inventor and discoverer in the manner of Athanasius Kircher. Not only did he publish all these works, it is his machines and techniques that Peers and Godley used when building their own spider-silk tapestry. Sadly I do not have the research chops to find any illustrations or descriptions of Camboué’s inventions online, for I’d love to find out more about him, (instead of just as a footnote to the current spider tapestry). By the way, you can see in the video, tantalizingly, a little of the devices used to harvest the dragline silk of the Nephila spiders.

The tapestry is on loan in the Chicago Art Institute’s newly renovated African art gallery, a vibrant and brightly lit environment that emphasizes the art in historical and geographic context. The tapestry itself is a wonderful example of living African art and culture, as the weaving itself is made with precolonial patterns of the local Madagascar Merina peoples, a tradition revived in part by Peers’ Lamba SARL weaving cooperative.

I am not sure where it is traveling to after Chicago, so if you’re anywhere near Illinois and want to gaze at the one-of-a-kind spidery wonder of the textile world, see it soon! ![]()

One Response to The Golden Fleece