This is my second post about our trip to Quincy.

Frankly, my Darlingtonia…

The native California pitcher plants (Darlingtonia californica) are a thing to behold, especially when they’re flowering. The blooms, hanging heavily from high straight poles, have flapping green sepals and petals veined with a deep bloody red. They’re as alien as the pitchers themselves, huge bulbous beasts that are actually heavily modified leaves. On our tour of the Butterfly Valley Botanical Area, I learned some new things about one of my favorite insect-gobbling plants.

The first is that the Cobra Lily (named for its unique pitcher, which resembles a hooded cobra) doesn’t have a pool of rainwater inside like Nepenthes and other pitcher plants do. Though it does generate a small amount of digestive enzyme, mostly it lets the ants, flies, bees, wasps, and other insects that get stuck simply decompose on their own. Slicing open a living pitcher, you could see the decaying remains of several kinds of insects, along with a few larvae, possibly a type of fly that makes its home inside the pitchers. After inspecting a total of three pitchers, we found at least two living maggots in each. So something can survive in there!

The second fact that was new to me was the circumstances surrounding pitcher plant pollination- it’s still a mystery! Though scientists some pretty good guesses, the full story still has yet to be researched, which is rather exciting. What botanist or entomologist wouldn’t want to work with pitcher plants? They’ve been a favorite of biologists and naturalists for hundreds of years, and I can’t blame them.

The other neat thing that I hadn’t really appreciated was how the translucent patches in the pitcher plants help doom their insect visitors. Known as areoles, these patches function just like windows in our own house, providing insects with a false escape. After wasting precious energy batting against the glowing roof while trying to fly up and out, the exhausted fly drops into the shaft below for a good slow sarlaac-style death.

The pitchers weren’t the only carnivorous plant Butterfly Valley had to offer. Along with bladderworts (which I sadly did not think to look for), The round-leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) also makes its home in the bogs, often in areas nearly entirely flooded with water. My fellow naturalists and I took care to watch underfoot, as the plants were tiny, and our hiking boots were only so waterproof. Eventually I found a series of fallen logs I could traverse, allowing me to get closer to these tiny insectivores. Crouching down, I could see that about 1 in 5 sundews had a gnat or tiny fly in some state of deceasedness affixed atop them, held fast by tiny hairs tipped in sticky digestive fluid. Most prey were pretty tiny, but Mrs. Swarm did find a crane fly, furiously hovering near the ground, putting up a terrific frantic fight for no discernible reason. It took careful observation to see that one of its long threadlike legs was wrapped around a grass leaf, and the tip of its leg stuck fast to a few minute sundew hairs. That’s some bad luck! But don’t feel bad, because for every consumed crane fly in Butterfly Valley, three hundred more seemed to take its place.

Haplessness Embodied

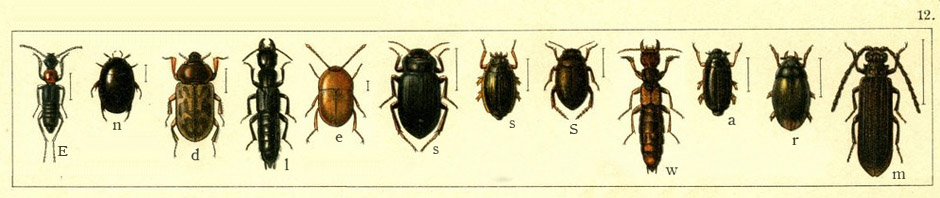

I’d prepared for mosquitoes on our trip, but instead I found crane flies. Oodles of them. In the forests, the fens, along the rivers, and in our hotel. They were everywhere! And so many species! Large red ones, thin scraggly ones, dark mysterious ones. Hiking around the fens I found the remains of crane fly pupae. The larvae of many species like soggy mud to loll about in, so it wasn’t surprising that this area would be crane fly central. Second to dragonflies and butterflies, they were the most populous insect of Quincy! If I was mayor of Quincy, I’d lobby to have the town motto be “Land of a Hundred Crane Flies!” But since my love of Tipulids probably isn’t shared with a single person in the town, it would be a hard sell. but I’m the mayor, right? So they’d have to go along with it. Because I love crane flies that much, I would be mayor of a small California logging town for them.

Perhaps it’s because they often get short shrift in guidebooks, which usually devote a single photo as representative of All Crane Flies. Plus everyone I know calls them “mosquito hawks” despite the fact that they don’t eat anything as an adult, so I always find myself leaping to defense of their eating habits. But mostly it is because as a frenetically energetic, long-limbed and somewhat clumsy organism, I share a kinship with something so utterly spastically hapless. We both flail around comically, waving our arms, running into walls, but gosh darn it we’re excited about something! Though I find myself envious of their stately halteres. I could sure use some gyroscopes, myself.

After our trips to the Botanical Area, we settled in at a nearby river to relax, and there found swarms of Western Swallowtails, checkerspots, bumble bees and other winged insects lappping up nutrient-rich puddles at the edge. I managed to catch an Oregon Tiger Beetle, and share it with friends under a magnifying glass, so they could get a sense of its ferocity. The river surface was full of mayflies and stoneflies that were just molting, some of them less successful than others. One aquatic insect somebody brought for me to ID, and I was stumped, even as to order. Stonefly? Dobsonfly?

California Alderfly

It took some work, but it’s the California Alderfly! I found two of them, black and beautiful. We also got to watch a couple of beavers hauling branches down to a riverside den hidden amongst the Indian Rhubarb and willow trees.

Sunspotting

But the main event of the weekend was the annular eclipse, and in the late afternoon our gang headed out to a large empty lot outside of Quincy, to gather, set up solar-filtered telescopes and pinhole cameras, and hand out solar-safe glasses to everybody within reach. My wife used a pair of binoculars to project the sun onto a large canvas sheet, and you could even make out the sunspots while the moon gobbled up the light. For a good 10 minutes the sun’s light formed a perfect ring around the moon, and we all hooted, clinked glasses of wine, danced about looking at shadows and laser-cut pinhole cameras, and stared awestruck into telescopes. Later that night (as we had for every night that weekend) we hauled up to above 5,000 feet to view globular clusters and galaxies in our friend’s telescope, and call out shooting stars as they went by while sipping hot cocoa. All in all, a well-rounded weekend celebrating natural phenomenae!

But the main event of the weekend was the annular eclipse, and in the late afternoon our gang headed out to a large empty lot outside of Quincy, to gather, set up solar-filtered telescopes and pinhole cameras, and hand out solar-safe glasses to everybody within reach. My wife used a pair of binoculars to project the sun onto a large canvas sheet, and you could even make out the sunspots while the moon gobbled up the light. For a good 10 minutes the sun’s light formed a perfect ring around the moon, and we all hooted, clinked glasses of wine, danced about looking at shadows and laser-cut pinhole cameras, and stared awestruck into telescopes. Later that night (as we had for every night that weekend) we hauled up to above 5,000 feet to view globular clusters and galaxies in our friend’s telescope, and call out shooting stars as they went by while sipping hot cocoa. All in all, a well-rounded weekend celebrating natural phenomenae! ![]()

2 Responses to Sundews and Sun Rings